STAMFORD -- We've all heard of the Salem witch trials, thanks in large part to Arthur Miller's play, "The Crucible." But Salem's saga wasn't the only witch hunt that blew through New England in 1692.

That same year, a Stamford house servant accused two women of witchcraft. And according to Richard Godbeer, a leading expert on witchcraft in the Colonial era, Stamford's story is a far more typical example of 17th century witch hunts.

The servant, Katherine Branch, lived with the Wescot family down on Stamford's shoreline, near Wescot Cove, according to Stamford Historical Society Librarian Ron Marcus. In April of 1692, Branch fell to the ground, her body contorting strangely, after returning from picking herbs. In the coming weeks, she would suffer several similar fits, convulsing, weeping and calling out hysterically. At first, the local midwife, Sarah Bates, examined Branch, concluding her illness could be due to natural causes. But after an unsuccessful bleeding -- a common medical practice for ailments in those days -- Bates concluded that Branch was bewitched.

Soon, Branch began relaying stories about a cat that spoke to her, offering to take her to a place where she could have fine things and meet fine people. In Godbeer's 2005 book, "Escaping Salem: The Other Witch Hunt of 1692," the University of Miami professor wrote that "sometimes, Kate declared, the cats turned into women and then back again, though who the women were she could not say."

At first.

"About a half a dozen people were accused in the beginning. That's not massive, but it's a significant number," Godbeer said in a telephone interview this week. Of that number, two women went on to be formally accused: Stamford's Elizabeth Clawson and Fairfield's Mercy Disborough. Like many of the cases in Salem, Clawson had personal ties with her accuser. The Wescot family and Clawson had feuded for several years, and Branch knew the family she worked for.

But unlike in Salem, where 19 witches were hanged, both women were ultimately acquitted.

"The villagers did not just assume blindly that just because Kate Branch was accusing women of witchcraft, they were guilty," said Godbeer, "They carried out a series of experiments to figure out why these women might perhaps be worthy of suspicion."

While history paints Puritan societies as overwhelmingly ruled by superstition and quick to finger-point, Stamford residents were actually very skeptical of Branch's story. And unlike many other witch hunts, Stamford's saga was recorded in a large amount of documents that still exist. From those records, Godbeer was able to piece together stories of villagers like Thomas Asten, who tested a theory that a bewitched person would laugh themselves to death if someone held a sword over her head.

To test his skepticism, Asten held a sword over Branch's head, and witnessed her laugh. But when a neighbor noted that Branch may have laughed simply because she knew the sword was being held over her, Asten tried again, more clandestinely. "This time she neither laughed nor changed her expression in any way," Godbeer wrote in his book.

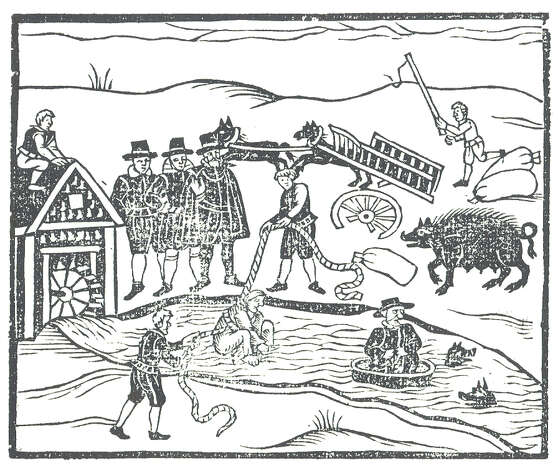

During the investigation, Clawson, who Marcus said lived roughly in the area of modern-day Washington Boulevard and Main Street, was even "ducked" in a Fairfield pond. Seventeenth century theory held that witches would float if their bodies were dropped into water with their hands and feet bound, while those who were not witches would drown -- a trial that usually proved more dangerous for the innocent.

But Clawson floated -- just as one would expect a witch to do.

But even after failing this test, a large number of neighbors continued to question Branch's accusation, and to assert that Clawson was innocent. In June, 76 Stamford residents signed an affidavit, stating that Clawson had never acted maliciously toward her neighbors or used threatening words. And after the case made its way through the courts in nearby Fairfield, it was determined that there was not sufficient evidence to convict Clawson of witchcraft, which was a capital crime.

"The reason this Stamford case matters is that most people's perception of 17th century New England witchcraft is based on the Salem witch hunt. New Englanders have a reputation of being trigger-happy, believing that being accused is the equivalent of being found guilty and executed," said Godbeer. "But that's not what happened in Stamford."

Much of Branch's fits can be explained away by modern science, Marcus said earlier this month. According to records, Branch's mother had also suffered from fits, which adds credence to a theory that it could have been a medical issue. But Godbeer said the real reason behind her fits have little to do with the story.

"It's really tempting when you look at someone like Kate Branch to ask, `Well, what was really going on? Was it epilepsy?' But I would argue that's precisely the wrong question to be asking," he said.

"Whether witchcraft exists or Kate Branch was faking or an epileptic or whatever is really, I think, the very least interesting thing one could possibly think about," he continued. "What matters is understanding what people believed and thought was going on, and what shaped their behavior."

maggie.gordon@scni.com; 203-964-2229; http://twitter.com/MagEGordon